.

Yet, why does this condensed space, typically between 2 houses, live 'large' ?

Creating a patio/terrace/deck garden room, below, again, I wonder, "what makes this small space live so large?"

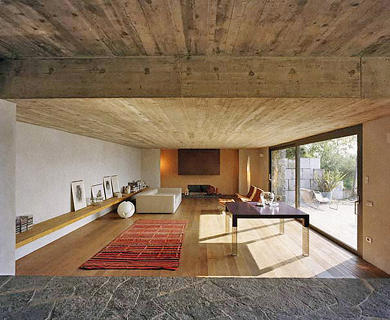

Inside, below, with a vanishing threshold into the garden, I ask myself, "Why does this room live so big?"

Years spent wondering why my little garden, surrounded much-too-closely with neighbors at every view, lives so entirely large. More, how does a small space live large AND feel like it's living on another continent in a different era?

.

Seriously, years. College degrees in engineering & horticulture, decades of reading garden/architecture books, decades attending garden lectures/symposia, with zero mention of small space gardens living large.

.

Slow, but the answer arrived. The sky. All of the above Garden Designs use the SKY as an element. Garden Design frames the sky. Better, you own the sky. No matter where the sky goes near your home, you own it.

.

Another word for 'sky' in Garden Design? Ceiling.

.

This is going somewhere important, stay with me.

.

High ceilings, in real estate, cost more money. Across cultures/era/continents humans pay a premium for high ceilings. Why? Science, now, has an answer.

"... participants were more likely to judge a room beautiful if it had a high ceiling compared with a low ceiling. But the greater insight emerged when Vartanian and collaborators studied brain activity. They found heightened activity related to high ceilings in the left precuneus and left middle frontal gyrus—two areas associated with visuospatial exploration. The left precuneus, in particular, has been found to increase in cortical thickness after spatial navigation training.

So another part of the appeal of high ceilings seems to be that they capture our visual attention and engage our desire to observe our surroundings. Vartanian and company ruled out other explanations based on the imaging data, including the possibility that high ceilings simply put us in a good mood. That idea didn't pan out because participants looking at high and low ceilings showed no fMRI difference in brain regions related to pleasure, emotion, or reward."...

.

Garden Design, using the sky, wields a potency to our brains we cannot produce ourselves. Amusing. Another tidbit from Providence, the first Garden Designer, and best.

.

Garden & Be Well, XO Tara

.

Pics, above, Pinterest board, Vanishing Threshold.

From Fast Company, the full article:

Why Our Brains Love High Ceilings

Not just for bragging rights.

One of the first things a realtor will point out to prospective home buyers or apartment tenants is a high ceiling. To many of us, anything above the standard eight-foot ceiling is a big selling point. In recent times, home buyers have tended to pony up for the amenity of nine-foot ceilings; in the abstract, when added heights aren't adding to mortgages or rents, people prefer their ceilings 10 feet high.

Part of the appeal of high ceilings is no doubt related to a general preference for space, but the behavioral and brain evidence suggests there's more to it than that. Some research from a few years back ties high ceilings to a psychological sense of freedom. And new neuroimaging work shows that a tall room triggers our tendencies toward spatial exploration.

"You can imagine that our enjoyment of rooms with higher ceilings could be due to these two processes working in tandem," psychologist Oshin Vartanian of the University of Toronto-Scarborough tells Co. Design. "On the one hand, such rooms promote visuospatial exploration, while at the same time they prompt us to think more freely. This could be a rather potent combination for inducing positive feelings."

A Liberated Mindset

A few years ago, marketing scholars Joan Meyers-Levy and Rui Zhu wanted to see whether the height of a ceiling had any impact on the way a person thinks. So they recruited test participants for a number of different experiments and modified the study rooms so that some had 10-foot ceilings and others had (false) eight-foot ceilings. Meyers-Levy and Zhu also hung up Chinese lanterns so participants would look up and, consciously or not, process the ceiling height.

Across several experiments, the researchers found evidence that high ceilings seemed to put test participants in a mindset of freedom, creativity, and abstraction, whereas the lower ceilings prompting more confined thinking.

In one test, for instance, participants in the 10-foot room completed anagrams about freedom (with words such as "liberated" or "unlimited") significantly faster than participants in the eight-foot room did. But when the anagrams were related to concepts of constraint, with words like "bound or "restricted," the situation played out in reverse. Now the test participants with 10-foot ceilings finished the puzzles slower than those in the eight-foot rooms did.

Another experiment asked participants to identify commonalities among a list of 10 different sports. Those in the high-ceiling group came up with more of these themes, and had their themes judged more abstract in nature, compared with participants in the low-ceiling group. Meyers-Levy and Zhu suspect this outcome emerged from the psychological freedom that comes with taller ceilings—a mindset that might also enhance creative thinking.

Altogether, they conclude in a 2007 issue of the Journal of Consumer Research, the research "shows that, by activating freedom-related or confinement-related concepts, ceiling height can be an antecedent of type of processing."

Ceiling Brain Scans

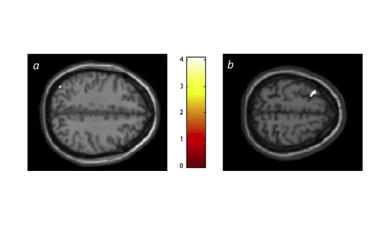

The new neuroscience study, led by Vartanian, had test participants look at 200 images of rooms while in a brain scanner. Half of the pictures showed rooms with high ceilings, half with low (below). Participants had an easy job: indicate whether they considered the room "beautiful" or "not beautiful." (The data actually came from an earlier study that looked at why our brains like curvy architecture, but were reanalyzed through the lens of ceiling height.)

Little surprise, participants were more likely to judge a room beautiful if it had a high ceiling compared with a low ceiling. But the greater insight emerged when Vartanian and collaborators studied brain activity. They found heightened activity related to high ceilings in the left precuneus and left middle frontal gyrus—two areas associated with visuospatial exploration. The left precuneus, in particular, has been found to increase in cortical thickness after spatial navigation training.

So another part of the appeal of high ceilings seems to be that they capture our visual attention and engage our desire to observe our surroundings. Vartanian and company ruled out other explanations based on the imaging data, including the possibility that high ceilings simply put us in a good mood. That idea didn't pan out because participants looking at high and low ceilings showed no fMRI difference in brain regions related to pleasure, emotion, or reward.

The findings, reported in a recent issue of the Journal of Environmental Psychology, should be considered preliminary given the study's limitations. For one thing, the test couldn't control for factors besides ceiling height that might have led to "beautiful" ratings, such as the lighting or color scheme or curved design. And, of course, people weren't physically standing in a room with high ceilings, which could change the experience.

But Vartanian says the research—in conjunction with the earlier work linking ceiling height and freedom—does add to our understanding of why people find high ceilings worthy of a real-estate premium.

"The combination of psychological and neural data can help us formulate a more complete picture of what is driving our choices," he says. "Knowing that people's preference for rooms with higher ceilings might be driven by the ability of those spaces to promote visuospatial exploration helps partly explain why people opt to live in such spaces, despite the fact that they cost more to purchase and maintain."